It’s a cliche to describe conditions as worse since the pandemic, and especially to make such proclamations about the sex industry. But every indication is that young Japanese women are now in a whole new world of sexual exploitation, however bad things might have been before. Japan’s economy, at least for its non-capitalist class, offered little hope after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, triple disaster of 2011, and prior decades of government austerity, but confidence was completely lost after the pandemic as businesses went bust, inflation surged, and employers escalated their campaign of hostility against a non-unionised and highly obedient workforce.

But this dismal state of economics explains only the background to the pandemic and its effect on young women in Japan’s sex industry. It characterises the problem in a way similar to that of Yumeno Nitō, director of Japan’s leading anti-prostitution outreach organisation Colabo, who sees pervasive despair caused by poverty, and feelings of hopeless resignation among young women caused by the normalisation of female sexual exploitation, as behind the shift.

But the plight of these women, perhaps now more than even before the pandemic, is clearly delivered by industrial and technological infrastructure that can be targeted by abolitionists to deprive pimps of their tools of trade. Generating political will to dismantle Japan’s sex industry, more than driving cultural or economic change, is an approach suited to post-pandemic times.

In this approach, anti-prostitution campaigners can draw on the authority of perhaps the world’s earliest statement of national condemnation of both the sex industry and its customers. Japan’s 1956 Prostitution Prevention Act was a law achieved by the country’s most politically astute women who squared off with pimps and sex buyers (literally in the parliament) to drive the sex industry out of business. Their task is yet complete, and campaigners in Japan today have a chance to take similarly direct aim at the infrastructure that underpins female sexual slavery.

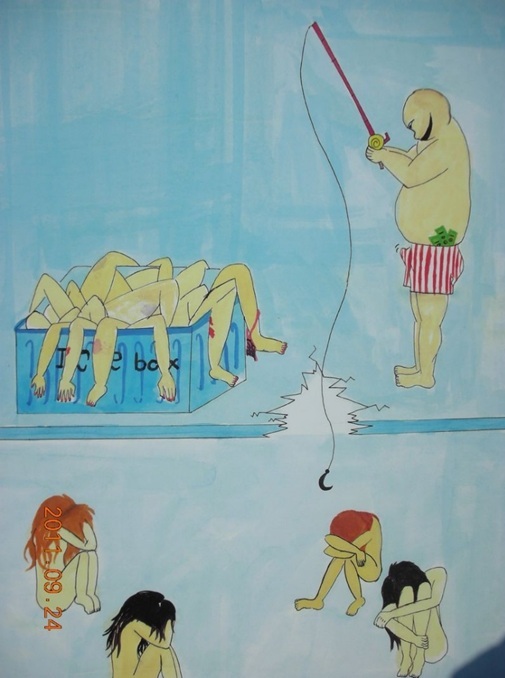

Before the pandemic, Japan’s sex industry—which is made up of both prostitution and pornography-production businesses—relied on a range of commercial enterprises for its procurement of young women. Different from that of nearly all Western countries, Japan’s sex industry incorporates few overseas trafficking victims. It is therefore reliant on domestic procurement.

Prominent among businesses meeting this need are so-called host clubs, which operate to lure star-struck young women into pseudo-romantic relationships with flashy young men for the purpose of racking up the debts that are used to blackmail them into prostitution. Originally the clubs operated as drinking venues for women with money to be flattered by young men serving drinks and flirty conversation. By the time of the pandemic (and still today), though, host club venues in their current form, rather than brothels, dominated the inner-city Tokyo red-light district of Kabukichō (home to an estimated 300 of 1000 clubs).

The district functions as a clearinghouse for Japan’s sex industry—its big-city lights are used to dazzle young women, often from regional areas, who come into the city after social media grooming, fleeing family abuse or chasing love, but end up homeless or in capsule hotels, and trafficked around the country.

Operating in tandem with these clubs are ‘scout’ syndicates that recruit young men from all over Japan to procure their female peers, mostly via social media. These syndicates are backed by organised crime, and the young men are schooled in techniques of victim entrapment, sometimes brutally. They liaise with brothels and sex businesses around the country to traffic young victims, and also to keep them in the sex venues. Scouts and their affiliate organisations earn kickbacks from brothel owners as long as women keep generating revenues. Scouts work with hosts to either funnel young women into clubs for the purpose of getting them into debt, or to traffic women out of clubs into brothels around the country.

A Kabukichō host was recently convicted for working with scouts to traffic 10 women this way. Another was arrested for concurrently (and violently) undertaking both the scout and host roles. Scouts spend their time scouring social media and dating apps for women in financial trouble with the aim of earning the brokerages that are offered by brothel owners for their efforts in cajoling and intimidating victims. They perform this trafficking role even for sex industry operators abroad.

Businesses operating to get young women into financial trouble are not limited to host clubs—there is also a ‘boy band’-style off-label music industry whose male talent sing and dance, but work even more assiduously to romantically groom young female fans who end up in debt after showing their love in the form of regular online payments. These young women are then primed to respond to ‘helpful’ offers of work from scouts on social media.

Internet technology now delivers pimps an efficient means of procuring women at scale. Since the pandemic, there are signs Japan’s scout sector has escalated its activities, possibly via internet technology allowing more efficient posting of women’s profiles for sex venue operators to bid on. While scout groups operated in Japan long before the pandemic, they tended to be made up of small numbers of locally connected young men who procured women in the real world rather than via social media.

But now Japanese police are arresting leaders of large-scale syndicates. In January 2025, two leaders of a group that had made roughly USD10 million over 4 years trafficking over 6000 victims were arrested, and, in the same month, the head of Japan’s biggest scout syndicate with 300 members that generated USD44 million in revenues via the trafficking of women into roughly 350 sex businesses around Japan between July 2019 and October 2024 was similarly indicted.

These arrests are significant but driven in part by a nationwide campaign against organised crime that was sparked by a series of violent home robberies (and of a Rolex watch shop in Ginza even more widely reported) perpetrated by men recruited on an ad hoc underground basis. Syndicates orchestrating the robberies (and also phone scams) are seen as a piece with scout groups, likely because of the sex trafficking revenues that gave them their capital base. To its credit, though, Tokyo Metropolitan Police have set up a taskforce specifically against the scout syndicates, the first of its kind since one launched in response to the Aum Shinrikyo cult back in the 1990s.

On the other hand, Japan’s judiciary has a history of handing down only suspended sentences to syndicate leaders, and this has supported their growth. Neither Japan’s police nor judiciary yet correctly understand scout groups as sex trafficking organisations—they are seen as criminal but only to the extent of breaching brokering provisions in Japan’s labour laws. Their essential role in the operations of Japan’s sex industry, given this industry’s reliance on domestic procurement, needs to be understood in order to see their complete eradication as an urgent goal of sex industry abolition.

Warning bells about the scout business have been ringing in Japan for years. In 2017, the dismembered bodies of 9 people were found in the apartment of a Kabukichō scout, Shiraishi Takahiro. They included 4 girls and 4 women, all drugged, sexually assaulted, murdered, and robbed, plus one man who became an incidental victim after visiting the apartment in search of one of the victims.

Earlier in 2017 Shiraishi had been convicted of a pimping offence but received only a suspended sentence. He procured seven of his eight female victims through social media, and killed the first 21-year-old woman rather than paying back money he owed her. He had earlier lured three other women to his apartment but did not kill them because he was able to use them financially.

Jun Tachibana of the prostitution outreach organisation Bond recognised the significance of Shiraishi’s perspective as a pimp and interviewed him on death row (where he remains today). In court, he had testified about the effect of becoming a pimp on his life. It led him to understand women as nothing but vehicles of financial and sexual gain, and this state of mind drove his crimes.

Indeed, young women do generate income for scouts and pimps in Japan, but only because large numbers of men are prepared to prostitute them. Research published in 2024 finds around half of Japanese men aged 20–49 having been sex industry customers, and these men perpetrating the behaviour an average of 6 times across their lifetimes. They have “higher income and have higher education” than other men, and so the means to financially underwrite the sex industry’s operations for their own benefit.

Researchers found that “ease of access, low stigma with respect to use of sexual services and the diversity in the type of services offered” explained relatively high rates of sex buying among Japanese men compared to male populations of other countries.

Reducing the ability of these men to contribute to the earnings of pimps and scouts through, for example, putting their social and financial standing at greater risk through penalties for sex buying would deplete the sex industry’s income stream and contract its operations. Demonising scouts, pimps, and sex-buyers as enslavers and sadists would further hamper the industry’s financial ability to operate on any larger scale, and would encourage public opinion oppositely in a direction of sympathy for victims as deserving of social support.

These victims now speak publicly about the horrors of Japan’s sex industry, and there is no shortage of evidence of carnage wrought by scouts, pimps, and sex-buyers in the country. In the western Tokyo city of Tachikawa in 2021, a 31-year-old prostituted woman was murdered by an underage sex buyer after he stabbed her 70 times in a hotel room after having “watch[ed] a film of people being murdered on the internet”. Media reports did not make clear whether the film was snuff pornography.

This murder, along with all the rapes, violence, humiliations, and abuses inherent to sex-buying, is made possible by the efficient operation of sex industry infrastructure, including smoothly running procurement networks, light social and legal pressures, and ample business ventures of many varieties. Putting spanners in the works of each of these is therefore the important task of abolitionists to protect women and raise their social status.

For all its weaknesses, the approach of Japan’s Prostitution Prevention Act in condemning pimps and sex-buyers while creating welfare services for victims is closer to the contemporary Nordic approach of abolitionist countries like South Korea than is widely recognised. The spirit of the Act has not had uptake in Japanese society for many decades, but the pandemic revived its relevance. It offers a clear solution to the problem facing Japanese authorities of destructive power wielded by organised crime and sex industry enterprises. This power depends on revenues, and these revenues are mostly generated by sex industry customers. While the Act does not yet incorporate penalties for sex buyers, even while it does condemn them, a simple amendment to introduce such penalties would deliver abolitionists a major weapon against the sex industry.

In a country like Japan with a population extremely sensitive to criminal and social sanction, even the hint of genuine penalty and opprobrium for sex buying as a socially unacceptable behaviour would significantly cut into industry revenues. The global drug industry, after all, finds Japan an impossible place to do business, despite the country having been awash with methamphetamine after the Second World War.

For the sake of young women at the mercy of debt, romance, and Japan’s sex industry, abolitionists must seize the opportunity that has arisen out of the pandemic to attack infrastructural bases of female sexual slavery, especially its scout/host trafficking networks and its sex-buyer financiers.